Osteoporosis (OP) is a relatively common condition affecting almost 3 million people in the UK with around 10% of these individuals (300, 000 per year) receiving hospital treatment for fragility fractures. Whilst it is commonly linked with the menopause (women tend to loose bone rapidly in the first few post menopausal years) it is a condition that can affect both men and women and has many other causes including inflammatory conditions such as RA and Crohn’s disease along with conditions that affect hormone producing glands such as an overactive thyroid; prolonged use of steroids can also increase the risk of developing OP as will a family history of the disease.

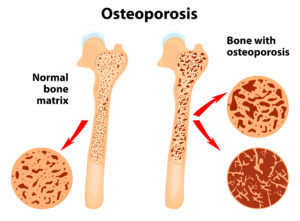

The thinning of the bone that precedes osteoporosis is known as osteopenia and is seen in the “honeycomb” shaped, central portion of the bone known as the trabecular bone; the condition becomes known as OP once a breakage has occurred as a result of this thinning.

The thinning process takes place because the activity of two types of cells within the bone alters,both with age and as a result of the above mentioned factors. These two cells are known as “osteoblasts” which build new bone and “osteoclasts” which break down old bone. In patients with OP the osteoclasts become more active leading to a gradual reduction in the density and strength of the bone.

The commonest fractures that occur in OP are those of the wrist, the hip and the spine all of which can lead to consequences that are often severe (43% of sufferers report chronic pain that they do not think will ever end) and debilitating (1 in 4 sufferers either gave up their job or reduced hours or changed jobs as a result of a fracture). In untreated individuals with OP the lifetime risk of fracture for a women is 1 in 2 and for a man is 1 in 5, which means that treatment is both important and strongly recommended. Fortunately for the vast majority of patients the treatment is relatively simple ( a weekly tablet or a yearly IV injection) and highly effective- the risk of spine fractures is reduced by between 55 and 70% and the risk of hip fractures by 41-47%.

Not surprisingly the medication used to prevent the worst affects of osteoporosis all act on the osteoclast cell activity and as such they act within the bone where these effects can remain for up to 10 years. The commonest medications come for a group of medicines known as “bisphosphonates” and are prescribed as either a tablet -Fosamax (alendronic acid) is the commonest one or as an IV injection Aclasta (zoledronic acid). There are also some newer medications such as denosumab (prescribed as Prolia) that again are in tablet form and carry the same risks as the bisphosphonates albeit for a shorter time period (it is believed that the affects of these medicines are removed within 12 months of stopping the drug use).

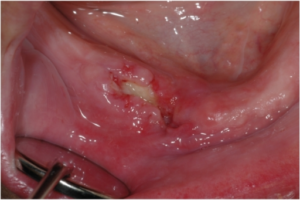

By now you may be wondering what all this information is doing on a dental website. Well the reason the two meet is that the commonest medications used to treat OP can have an impact on the jaw bone that is often seen after a tooth is extracted or in the presence of chronic infection such as gum disease or dental abscesses.An unfortunate and only recently recognised side effect of the drugs used to treat OP is is a condition known as ONJ (osteonecrosis of the jaw) that represents as a persistent site of necrotic (dead) bone that fails to heal following either a tooth extraction or a site of chronic dental infection. The condition is very rare but can be severe and debilitating with pain , swelling, loss of function and nerve damage to surrounding tissue being seen in the worst cases.

The risk of a patient who takes any of the above medications for OP developing a problem with ONJ are very low with the incidence being recorded at between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 100,000 which is clearly many, many times lower than the risk of a fracture to the wrist, hip or spine in patients with OP who do not take any medication for it. There is another group of patients who take bisphosphonates, however, and these patients take much, much higher doses and so have a significantly increased risk of ONJ; these are the oncology patients receiving treatment for bone cancers. The commonest cancers that receive this treatment (usually as weekly or monthly IV infusions of zoledronic acid but also with certain anti-angiogenic drugs that have the same risk of side effect) are prostrate and breast cancer (both cancers see as many as 70% of patients go on to develop metastatic bone disease) along with myeloma which is a cancer that arises from the plasma cells ( a type of white blood cell) in bone marrow. In these conditions the drugs listed have been seen to be hugely effective in reducing both the spread of the bone diseases and the pain caused by these conditions and so form an essential part of these patients care. Sadly we also see an almost 100 fold increase in the risk of ONJ in these patients and so might expect to see it in between 1 in 100 and 1 in 1000 individuals receiving this treatment.

One of the hardest thing to do in medicine and dentistry is to try and assess the individual risk that a single patient faces when taking medication or suffering with a particular condition and ultimately we can never predict with any certainty what will happen to any one patient given the known risks; all we can do is give upper and lower estimates and a “best guess” as to what is the right thing to do. Based on the above figures however it is clear that any patient with an increased risk of an osteoporitic fracture should not be deterred from taking medication because of a fear of developing ONJ.

Remember that a women with osteoporosis who does not take medication has a 50% or 1 in 2 risk of a fracture over her life time where as a women with osteoporosis who does taken medication would expect to reduce this risk by between 41 and 70%, depending on the site of fracture and type of drug, but would have a risk of only 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 of developing ONJ. I know that the numbers can seem complicated but a 50% risk of a fracture versus a 0.001% risk of a complication makes the argument for taking the drug, on dental grounds at least, very compelling.

For all patients who take any of the medication mentioned we recommend the following care: regular hygiene and prevention work to reduce the risk of developing a dental problem that might lead to extraction or infection and let us know straight away if you have any problems with pain or swelling around a site of any dental treatment. Smokers who take these medicines are at an increased risk of ONJ compared to non-smokers as are patients who need to take steroids or immunosuppresant therapy. At StoneRock we run a specific “at risk” care protocol for patients who might be affected by this condition and work with all of our patients to ensure that we are doing all we can for them to lower their risk of decay or gum problems.